Tips and tricks – Leveling the playing field for MD SMEs (medical device small-medium enterprises)

Note: this article is written with mostly medical device legal manufacturers in mind. The applicable parts of the content are also considered valid for contract manufacturers and other medical device-related service suppliers as well (e.g., sterilization providers).

1. Recognize that some of the current regulatory requirements don’t scale linearly with the size of the company and the number of different product groups

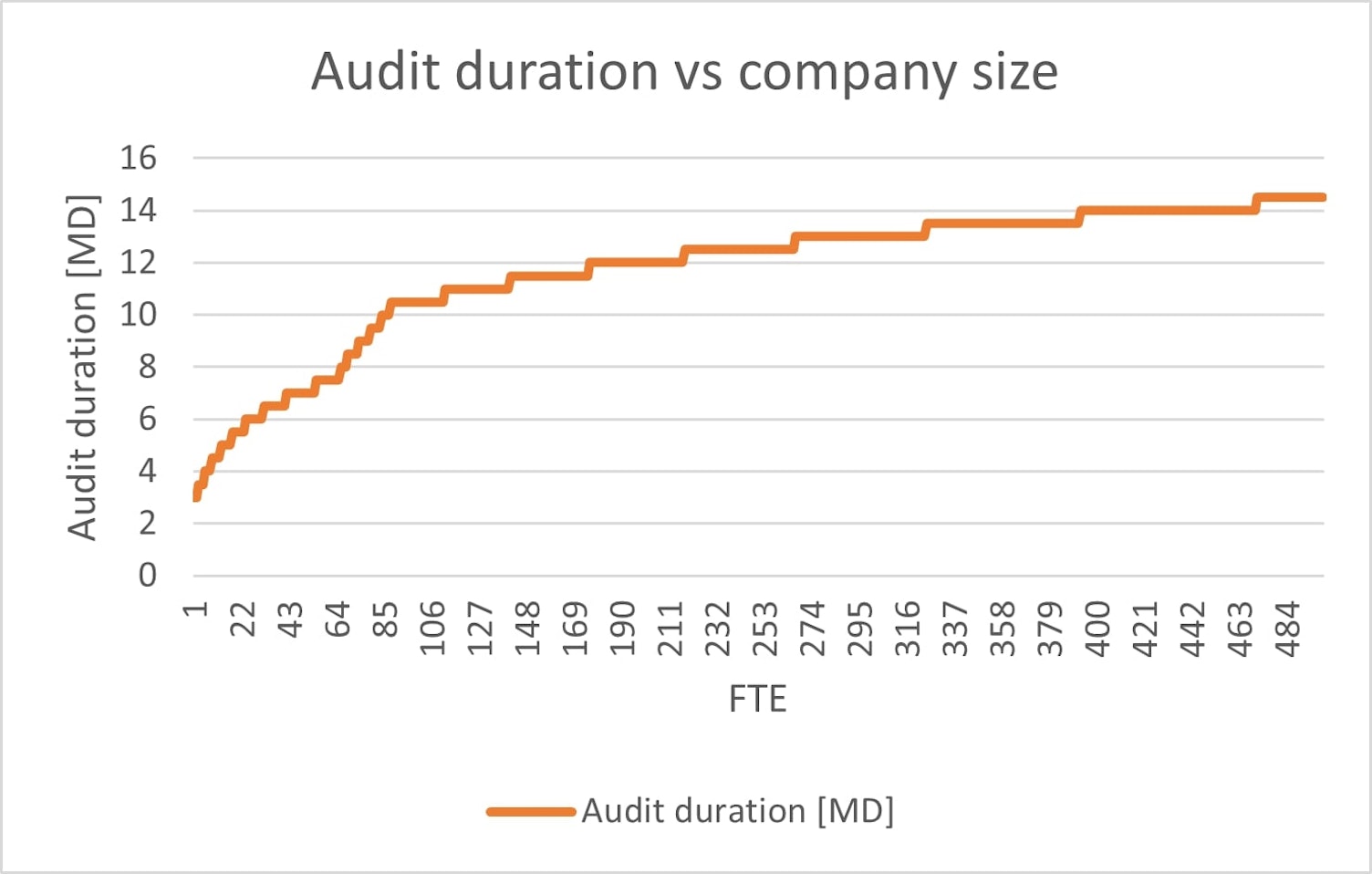

For example, based on the IAF MD9 Annex D, we can see that the audit durations plotted against the company size (expressed in full time employee equivalent number) is heavily hyperbolic (rather than linear), and is especially steep in the SME company size (1-100 FTE1) range. The initial audit of a company with 10 employees is 4.5 mandays2 (out of the ~2000 working day in a year, assuming the audit requires 2 people for the duration of the audit, the company spends 0.45% of the time being audited), while the duration for a company with 500 employees is 14.5md, even assuming 3 employees participating in the audit, they only spend 0.043% of their year in audits (~1/10th that of the smaller company).

____________________________

1full-time employee equivalent number

2one manday (or md, MD for short) is typically an 8-hour working day

Similarly, in schemes where technical documentation reviews are sampling based (e.g., MDD, MDR, UKCA Class IIa and some IIb products), the percentage of technical documentation to be sampled throughout a 5-year period is much less for a large company with 100+TDs3 and thousands of models (e.g., 17 TDs to be reviewed during the review cycle, which is 17% of the TDs) than an SME with just one or a few related products, which all need to be reviewed (100% sampling).

The IAF MD1 document further allows the sampling of certain additional sites as well. For medical device manufacturers, sites performing design or manufacturing activities cannot be sampled, but service centers can, for example.

2. Understand that SMEs may have different missions and can be in a different current state, which may impact their efficiency

Some startups are either established by or, early on, discovered and coached by larger manufacturers. This allows the well-established manufacturer to experiment with certain technologies and products without tarnishing their main brand, should the startup’s product flop. These SMEs often get support from their mentors (e.g., direct financial support, RA/QA4 consultation, access to certain tools, etc.), and their exit strategy clearly points towards being acquired by their big brother, once their product receives market approval(s). In many cases, such a startup only comes up with the product, but the product realization (manufacturing, service, installation) and distribution networks and supply chains are outside the scope of interest or expertise of the aspiring manufacturer.

By contrast, some SMEs are founded by an independent person or group, and are run independently, in many cases without a clear exit strategy, existing in a startup phase for years or decades with small, organic growth.

As for company sizes, viable ones include small ones (1-30 FTE) and medium-sized enterprises (100-500 FTE), with the in-between gap (30-100 FTE) generally considered an unsustainable valley of inefficiency (too big to micromanage with informal communication and generalist roles, but too small to have dedicated roles for every function, characterized by constant organizational changes and restructuring), and many manufacturers strive to quickly reach their next growth milestone.

____________________________

4technical documentations

3regulatory affairs / quality assurance

3. Product strategies for SMEs

SMEs typically have very limited resources to reach their mission. As such, they must very carefully allocate funds to get the most out of their investment. Depending on the context in which the SME exists (e.g., startup waiting to overcome the valley of death5 vs. a steady family business that already generates a modest but sufficient revenue), such manufacturers usually have to focus on establishing, maintaining or increasing their revenue and market share.

For a startup, the primary directive is to have at least one product reaching the MVP6 stage that can be monetized, which can in turn attract more funding and growth. There are many pitfalls to avoid, including diluting the product offerings, feature creep, and being overly optimistic about certain milestones or the competition’s presence. A precise regulatory strategy (including rollout sequence) is essential. Any vaguely defined item (e.g., product languages) is expected to bite back in the most unfortunate moment and may hinder (or halt) the market access of the product.

For more well-established SMEs with an existing product portfolio, the offerings have to be (re)evaluated to decide which products sell well in which market. If multiple products need market approval, it should be considered if all products need to undergo a conformity assessment at the same time, or a staggered release (the best-selling one starting to generate revenue financing the conformity assessment cost of the other products) is more beneficial. On the other hand, the manufacturer should also make swift, fact-based decisions about discontinuation of low-selling products where necessary.

Many manufacturers feel competitor pressure and when they are uncertain whether their devices are regulated as medical devices in their target markets, they are under the impression that they should follow their competitors and should force their products to be certified as medical devices or apply some tactics (e.g., exaggerated intended use and indication claims) to drum up the classification of their device. It should be noted that most regulatory approvals are not marketing tools, and smart SMEs don’t treat them as such (as usually the conformity assessment of higher risk medical devices costs more than those in the lower risk class, and surely more costly than self-declaring the product without NB conformity assessment). Such false or semi-true claims are liable to being challenged at any time during the lifetime of the product, which is a risky foundation to build sustainable growth.

___________________________

5the “valley of death” of a startup is typically the early investment period before the venture generates sufficient profit and cash flow to break even

6minimum viable product

4. QMS (Quality Management System) best practices for SMEs

When setting up the QMS of a SME, the manufacturer should consider their current and future needs. Similar to shooting for an MVP product, the QMS processes and tools should support the business, not the other way around (e.g. databases that are just manually fed without providing useful business information). Generally, the simplest tool and process that provide the necessary information and control (e.g. a fixed jig representing a physical dimension for product quality testing versus a complex measurement apparatus or an ad-hoc email group message versus formal regular meetings with a broad audience) will likely provide the best value and should be selected. The ISO handbook: “ISO 9001:2015 for Small Enterprises - What to do” is a valuable resource in tailoring the QMS to meet the requirements with resources typically available to SMEs (even though it is written for general SMEs, the principles mostly apply to ISO 13485-based medical device manufacturer management systems as well).

For maintenance, calibration, pest control, product safety testing and similar services, it should be noted that to some degree, the manufacturer is indeed in control of the specifications of these services and the extent that can and should be negotiated with the service provider. For example, if a given measuring equipment (e.g., a caliper) is only used for a dedicated purpose and a limited range, it is sufficient to calibrate it for that range (the fewer calibration points can mean cost savings without sacrificing the use value of the equipment). Similarly, while initial recalibration intervals are usually based on the equipment manufacturer’s recommendations, subsequent calibration intervals can be adjusted with plausible justification (e.g., based on ILAC-G24, Guidelines for the determination of calibration intervals of measuring instruments or the NCSL International RP-1, Establishment and Adjustment of Calibration Intervals). For some measuring equipment that is inherently not susceptible to going out of tolerance (unless visibly damaged, e.g., measuring tape, glass measuring cups) or not used for qualifying measurements (e.g., scale to determine the postal weight of shipping parcel – considered reference measurement), the equipment may be designated “No periodic calibration required” or “NPCR”. Other manufacturers choose factory calibrated equipment that they simply replace upon the expiry of the calibration (which in some cases is cheaper than recalibration).

For SMEs there is usually no need for separate management systems to meet various regulatory or standard/process requirements, the processes can be integrated into one, (ideally Lean7) management system. In most cases, the implementation of practices from other management system standards (e.g., environmental, social responsibility and governance – ESG; information security or occupational health and safety) can be helpful but their use (formal implementation and certification) is optional.

When designing a QMS documentation structure, the manufacturer should consider several factors, such as: compliance with the requirements (where it has to be recognized that the external parties seek information as evidence and so far as it’s clearly available, most of the time they don’t care about the form and structure of the documents), ease of implementation (e.g. a full set of “boilerplate” SOPs ready to be dropped by the consultant might be quick but might not represent the SMEs activities without extensive customization) as well as ease of maintenance (how fragmented are the process descriptions vs how often they have to be revised).

Often, manufacturers swerve off the optimal path by choosing either too sophisticated tools/processes (thinking that when they grow, it will be available) or cutting too many corners (e.g., choosing poor quality tools that have unsustainable levels of maintenance).

Most of the time, ongoing costs of subscription-based services (e.g. SaaS8, IaaS9, etc.) are more predictable and favorable for SMEs (compared to the upfront investment of buying all necessary tools and infrastructure), however, a cost-conscious SME should always consider the total lifetime cost of their resources (infrastructure and equipment, technical standards, human resources, computer software, services, etc.). For many SMEs, keeping track of things in an Excel spreadsheet works just as fine (or better) than a half-customized fancy ERP system, especially if they know that they will be acquired within a few years and the new owners will impose new processes and tools to fit into their new corporate context.

The various standards and regulatory requirements almost always require a risk-based approach. It is crucial for the SME to learn to consistently justify their actions and risk-based decisions (e.g., frequency of activities, level of control), in writing. This can save the company considerable resources and prevent many uncomfortable discussions during subsequent audits.

When it comes to human resources, the manufacturer should carefully weigh their core competency (what is it that only they can do and will add value to the product) and consider outsourcing everything else, especially processes that require missing competency, extensive infrastructure or tooling. Whatever functions the company retains internally, they should set realistic (not too low, but also not too high) competence requirements (including a clear distinction between required and optional skills, ability, knowledge, and experience) and ensure that those are enforced and ensured. For small companies, some roles are shared, and multiple roles might be assigned to the same person (including various top management functions). In such cases, the principle of impartiality (conflict of interest) should be considered, i.e., personnel should not check their own work (e.g. if the internal audit is performed only by one consultant, the next year they should not do the whole internal audit, especially not the internal audit of the internal audit process). For training, the manufacturer should consider a train-the-trainer strategy, in which only a select few employees are externally trained (which is usually quite costly), who in turn train further employees in-house.

A crucial and niche set of required competencies is those required to comply with the quality and regulatory expectations. The manufacturer should consider whether it is more beneficial for them to have these functions staffed by internal resources vs working with a consultant.

When applicable (e.g., if the manufacturer’s key asset is their unique technology), the make or buy decision (and the supplier selection) should also consider the manufacturer’s exposure of their intellectual property. In many developed countries the protection of intellectual property only goes as far as the owner can enforce it, which can often put SMEs at a size and resource disadvantage.

During product realization (in particular the manufacture/production, installation and service processes), most manufacturers neglect the possibility of releasing products under concession (e.g. a small cosmetic defect on a device that still complies with all applicable regulations), which in some cases can reduce the cost of quality (nonconforming products scrapped or reworked).

Once the QMS is established, in most cases manufacturers have a choice of whether or not to get their QMS certified to various requirements. As with the implementation, the golden rule here is also to only get the services that the manufacturer truly needs for their current products and their current markets. For example, an MDSAP (Medical Device Single Audit Program) certification can be used as an ISO 13485 certificate; an ISO 13485 certificate is generally optional, unless required by the manufacturer’s customers (typically the purchasing department of the healthcare provider). For SMEs, typically it is a good idea to try to consolidate all their certifications under one certification/conformity assessment body, and try to synchronize the due dates (the date around which their audit is performed each year) across all certification cycles, even at the expense of “losing” some months of certificate validity (e.g. if one certificate is valid for 5 years, and another for 3 years, it is beneficial to renew the 5 year certifications during with the recertification of the 3 year validity certification; this way, over a 15 year period, there will only be 5 recertifications vs the 7 if the cycles are not synchronized).

___________________________

7Read more about Lean principle and methodology: https://www.lean.org/explore-lean/what-is-lean/

8Software as a Service, like some cloud-based applications such as Microsoft Office 365

9Infrastructure as a Service, such as cloud computing (e.g. Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure) which often has clear benefits over the manufacturer trying to purchase and properly (i.e. safely) configure and maintain (and scale) their own IT infrastructure.

201 Route 17 North,

7th floor,

Rutherford, New Jersey, 07070,

United States